Chinese Market Situation

Operators

Chinese companies are aggressively competing for territory and investment. Mobike and ofo are currently the two biggest player in the industry with a combined market share of 90% in China (see here). In March 2018 both ofo and mobike slowly ended their price war and drastically reduced the number of free bikes showing that they had gained a strong user base, but criticism of users followed directly (see here). However, problems are persisting, shown by the fact that the Chinese State Administration for Industry and Commerce noticed a 750% spike in rental service complaints, 64% of those complaints were linked to bike sharing services (see here). As of the beginning of 2019 most of the bike share operators are either bankrupt or struggling financially.

MOBIKE

In December 2017, mobike already had more than 7,000,000 bicycles and more than 200,000,000 registered users in 200 cities in 12 different countries. In October 2017, mobike entered into a partnership with the ‘China Council for the Promotion of International Trade’ to ease the expansion into countries abroad (see here). Mobike is partnering with seven Chinese cities (Beijing, Tianjin, Shijiazhuang, Ningbo, Nanchang, Guiyang and Shenzhen) to use their bike sharing data for urban planning (see here).

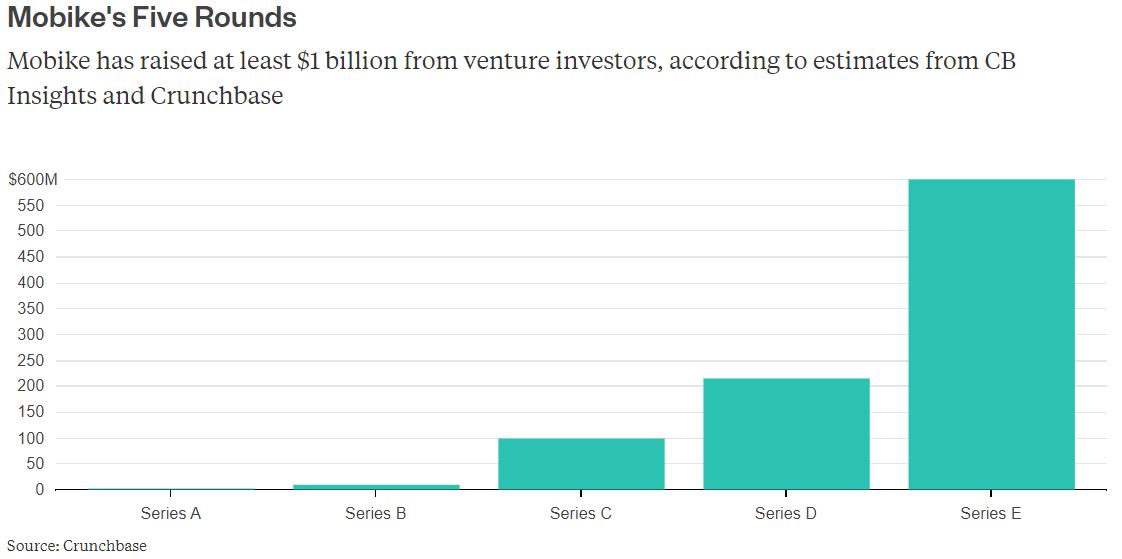

By October 2017, mobike had raised at least $1 billion with one of its main investors being Tencent (see here). At the end of January 2018, it was announced that mobike had raised another $1 billion of funding (see here and here). Investors of mobike include Tencent, Temasek, Foxconn, Sequoia, TPG and Hillhouse Capital.

In April 2018 mobike was acquired by by the food-delivery giant Meituan-Diaping which has been one of the main shareholders of Mobike for 2.7$ billion (see here). Meituan is China’s biggest online services company which combines food delivery with other online-to-offline services and recently moved into ride-hailing: The deal gave Mobike an enterprise value of about 3.7$ billion (see here).

However, around the same time a Financial Times article stated that mobike burns 50$ Million per month for its operations. This is partially due to the policy to offer subsidies to woo new customers has left Mobike with heavy losses as it battles against Ofo. These in turn have led to an estimated $1.3bn of liabilities on its balance sheet, the bulk of which represented customer deposits (see here).

As a result, mobike has been preparing to sell its European branch for 100$ million since the end of 2018 and the operator is already working with a greatly reduced fleet which can especially be noticed outside of China where most of mobike’s operations are closed (see here).

OFO

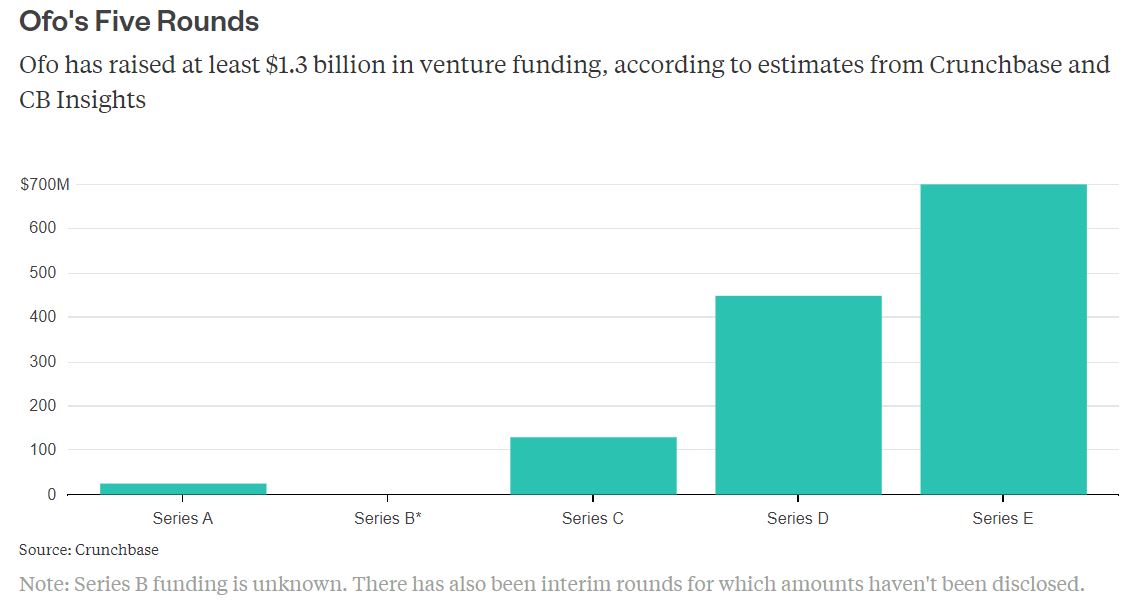

ofo is the other main operator in China. In July 2017 ofo finished its series E founding with $700 million that was mainly backed by Alibaba (see here).In December 2017 it was announced that ofo received an additional funding of $1 billion, partially funded by Alibaba (see here). In January 2018 the company was valued at $10 billion and it was made public that Alibaba had purchased shares worth $3 billion from GSR. This makes Alibaba one of the main shareholders besides Did Chuxing (25%) and the two co-founders (see here). In February 2018, ofo pledged its shared bikes to Alibaba affiliated companies in order to receive an additional $280 Million in funding (see here). In March 2018 it became known that ofo had secured another round of funding worth $866 million primarily backed by Alibaba or its affiliated companies (see here).

Since the end of 2017 there have been multiple reports stating that ofo is in financial problems resulting in laying off workers and not being able to pay the bills to the bicycle manufacturers. Moreover, there are rumors that ofo is using deposits to finance itself. So far, the company is denying all claims. In December 2017 it was reported that ofo only had 53$ million in cash left and had already used more than 466$ million to finance its business (see here). Added to that is a Financial Times article stating that offi is burning 25$ million a month to finance its business operations (see here). The rumors continue and in June 2018 an article appeared that reported about alleged mass layoffs at ofo and the misappropriation of users’ deposits. This is due to the fact that ofo owes about 1.2 billion yuan (roughly 155€ million) to its suppliers but that the available cash balance is less than 500 million yuan so users’ deposits are used to pay for the running costs of the company (see here).

In a next step one supplier of intelligent lock services to ofo has complained that their bills have not been paid for the past half a year. As a result, the intelligent lock company is threatening to disable all their ofo locks that are currently in service, which would render three million ofo bikes useless. Also bicycle companies such as Phoenix and Flying Pigeon have started to complain as their orders have more than halved.

In China, ofo users have also started to feel the financial burden of the company as ofo’s deposit free policy is slowly being cancelled in Chinese cities and prices are being increased. Moreover, many users that would like to get their deposit back are not being refunded due to the immense cash flow problems of ofo (see here).

Outside of China, ofo ceased its operation in many countries in 2018 including in Australia, Austria, Germany, India, Israel, Spain, Thailand and the UK.

OBIKE

oBike is a bike share provider that is based in Singapore but its bicycles are produced in China. In December 2017, the company was active in over 60 cities across 17 countries (with a big presence in Europe). Their goal is “reducing the amount of single owned bikes on the streets” by establishing a franchise business model in cooperation with local businesses (see here and here). In January 2018 oBike entered into a strategic partnership with the ride hailing company Grab. “oBike will integrate GrabPay into its app, offering its riders another cashless payment option and the ability to earn GrabReward points. Grab branding will also appear on its bikes (see here).

In June 2018 it was announced that oBike had suddenly stopped operations in its home market and that the company would go into liquidation. Reasons cited were much more vandalism and illegal parking resulting in stricter regulations and many fines for the company. It was not mentioned what would happen to oBike’s operations in Europe (see here). Many users are already experiencing problems to get back their deposits (see here).

Hellobike is currently the third biggest operator in China, the company mainly focuses on second and third tier cities. As of January 20, 2017 Hellobike was operating in 160 cities with almost 100 million users. However, the company has not expanded out of China yet (see here).

Bluegogo’s bikes will now be taken over by Didi Chuxing, famous for its ride-hailing serivce, that entered the bike sharing scene in mid-January 2018 as well. Cyclists in Beijing and Shenzehn can use ofo and Bluegogo bikes with the latest version of the app (see here). At the end of January 2018 it was announced that Didi Chuxing was also operating its own shared bikes titled Qingju in Chengdu (see here).

At its highest peak there were 70 bike share operators in China but by February 2018 already 20 of those had closed down (see here).

Presence in China

In Shanghai alone, 1.5 million shared bikes were circulating in November, about 1 bike for every 16 citizens (see here). At the end of October 2017 the number of bikes had dropped to 1.1 million because operators were forced to remove bikes that were in a poor condition (see here).

In Beijing in September 2017, 15 different operators had about 2.3 million shared bikes in the city, but the addition of further bikes has been banned (see here).

Diversifying their Business

At the beginning of 2018 several bike sharing operators have started to further diversify their businesses in order to say afloat. One common plan is to also offer e-bike sharing services in the future.

In January 2018, mobike announced that it would enter the ride hailing market with a small pilot project in the Guizhou province (see here).

Around the same time it became known that oBike would also offer small delivery services under the name oBike Flash (see here).

Chinese Regulatory Response

One of the first reactions in many Chinese cities has been to seize shared bikes that had been vandalized or were illegally parked. This has led to immense bicycle graveyards with thousands of shared bikes (see here).

“In May 2017, China’s national-level Ministry of Transportation drafted the first country-wide framework for regulating dockless bike-sharing, issuing a formal regulation in August 2017. This new law regulates bicycle and traffic standards, punishing individuals for illegal behavior as well as requiring local governments to ensure an even distribution of bikes and to set up designated parking spaces.

Since then, nearly 30 Chinese cities have passed regulations to guide bike-sharing’s production, operation and maintenance, adhering to the national guidelines (see here). Those cities have often more stringent criteria such as requiring an annual check-up of the bikes, a minimum amount of maintenance workers and making operators responsible for cleaning up their bicycles (see here).

Shanghai was one of the first cities to such take city-wide action by drafting a law in April 2017 and issuing it in October. “The guidelines push local authorities to integrate bike parking with city planning requirements. It requires operators, government officials and agencies to control the city’s bike fleet, such as requiring bike plate registration, banning shared electric bikes, and guaranteeing better parking by using Geo-fence technology”. In addition, a cap is set on the maximum number of bikes allowed. “The regulation also protect consumers financially. The city appointed an independent financial institute to oversee bike users’ deposits, assuring that they’ll receive their money back of a bike share operator goes bankrupt” (see here).

Tianjin, a city know for its many bicycle producers, also quickly noticed that the oversupply of shared bikes posed a problem for the city. In May 2017, several municipal agencies of Tianjin published the “Tianjin Internet Rental Bike Interim Measures”, a set of regulations defining roles and responsibilities for operators, users and the government itself. The regulation went into effect in October 2017. The regulation requires orderly parking, quality and timely maintenance of the bikes, sharing standardized data with the city, transparent and secure user deposits as well as clear rules and enforcement (see here).

Nanjing decided in August 2017 to make licenses mandatory for operators starting in 2018 (see here).

In January 2018 Shenzhen forbid bike share provider Didi Chuxing to put their Bluegogo branded bikes on the street because the bikes and users’ deposits are not up to standard (see here). Overall, Shenzhen has very strict regulations for bike share providers and a recent assessment showed that the operational management of bike share providers is often very poor (see here).

To really tackle the problem of overcapacities many cities including Shanghai, Beijing and Guangzhou even banned the addition of further shared bikes (see here).

In the spring of 2018 Beijing implemented electronic fences to make sure that the bikes are parked in an orderly fashion. Previously parking guidelines were issued but not properly enforced (see here).

Deposits

In February 2018 it was announced that China’s Ministry of Transport, the People’s Bank of China and the China Banking Regulatory Commission had drafted a law to regulate the deposits of bike sharing services. The bankruptcy of bike sharing operators led to a loss of CNY1 billion in user deposits and much more is held by the bike companies.

The new guideline proposes three options: renting bikes without deposits, refunding the deposit right after a bike is returned or operators that require deposits need to establish a separate account for their deposits that is subject to government scrutiny (see here).

Economic Problems

The business model of dockless bike sharing does not offer economies of scale and is very capital intensive. So far none of the Chinese operators have made profit yet despite big investments. There are many articles being written about how unsustainable the whole business model is because it is cheaper to deploy a new bike than to fix a broken one (see here and here). Thus, many presume that the real business model is gathering data which was confirmed when journalists found a big data leakage with the operator oBike in November 2017 (see here and here).

Bike share operators are burning money fast and in December 2017 rumors emerged that ofo only had $53 million in cash left, while mobike still had $1,086 billion left. Each have supposedly spend more than $466 million of their deposit founds to finance their business. However, both companies deny these allegations (see here).

The third biggest company Bluegogo went bankrupt in mid-November 2017. But this is not the only company, in 2017 five Chinese bike share operators went bankrupt and $150 million in deposits could not be refunded to users, as it seems that deposits are often used to advance the business (see here and here). Due to problems with paying back deposits when an operator is going bankrupt, the Chinese Consumer Association is now asking for stricter regulations on deposits (see here).

Funding

The companies are able to be in business thanks to billion worth investments from various tech companies.

In January 2018, it was announced that Hellobike would secure another round of investment, worth about $1 billion. One of the investors is rumored to be Ant Financial, an affiliate of the Alibaba Group that has heavily invested into ofo (see here).

Threats to the Bicycle Industry

There is a high risk of overcapacities in the market because the current trend is that the operator with most bikes is the leader and actual profit is less important (see here). For example, ofo has ordered 5 million bicycles from the producer Phoenix for the next years (see here).

As a result, overall sales of bicycles have decreased in China, in some regions the total sales volume in the local market are declining by 60 or even 70 percent forcing them to shut down or to look overseas to make profit (see here and here). Mobike has built its own production site with an dailyproduction capacity of 50,000 bikes, nearly a third of global production (see here and here). This shows that both, bicycle retailers and manufacturers are facing the same problem.

When Bluegogo went bankrupt in November it left behind a debt of $1.51 million for the local supplier and as previously mentioned Bluegogo was not the only company to go bankrupt in 2017 (see here).

Moreover, the oversupply of shared bikes are disrupting local supply chains, driving up the price of bike components and are hindering brand awareness (see here)